Ancestral Research

In the series Ancestral Research, three female figures emerge who at first seem to represent biographical cornerstones of a family history, yet they undermine the logic of genealogical storytelling. The images carry documentary credibility, while the texts construct a fictional world in which historical violence is partly erased, partly shifted, and partly replaced. What matters is that the series does not create an intact or healed world. Instead, it inscribes alternative forms of injury — wounds that cut just as deeply. In the biographies of the two mothers, the historical catastrophe of the twentieth century disappears, but violence itself does not.

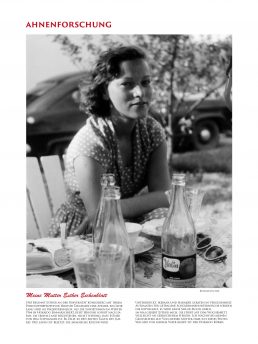

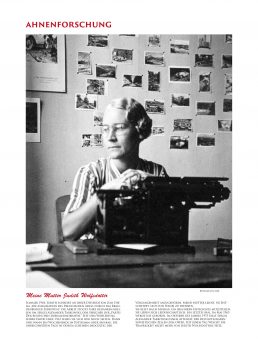

Esther loses the great love of her life in the turmoil of a completely reimagined political landscape. Judith is traumatized by a political assassination; her intellectual work is destroyed, her personal future broken. Both women are freed from the specific historical violence of National Socialist persecution, yet their lives remain marked by loss, destruction, and existential rupture. The series is therefore not a utopia in any conventional sense, but a displacement of catastrophe: the trauma moves, but it does not vanish. This is the double-bind at the core of these works. The names — Jewish first names paired with exaggeratedly Aryan surnames — mark a world in which the ideology of real history has lost its power. But even this world is not unscarred; it is wounded differently. The genealogical utopia is fragile, not whole.

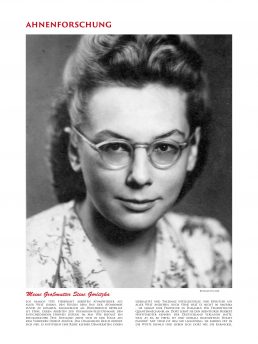

Against this backdrop, the third figure, the “grandmother” Stine Gorlitzka, appears almost like a break — or a later shift in paradigm. Her biography contains no tragic core. She is neither victim of political systems nor subject to external violence; she is not persecuted, not abandoned, not betrayed. She carries no invented or displaced wound. Her story is full of vitality: a breakthrough in physics, the almost cheerful absurdity of scientific discovery, a life that unfolds sexually in the desert — unbroken, overflowing, even comically abundant. She is not traumatized but unbounded; she stands as a defiantly joyful counterpart to the two wounded mothers. Her life contains something unexpected: a utopian surplus that escapes historical logic altogether. Her world is not one in which violence has been transformed; it is one in which it scarcely exists. It is as if the series reaches a different narrative state here: away from the reconstruction of alternative tragedies and toward a formal freedom that allows suffering simply not to be reintroduced.

In this shift, the deeper structure of the series becomes visible. Ancestral Research is not a consistent genealogical system but a reflection on the modes of origin: replacing trauma, overwriting trauma, dissolving trauma. The two mothers carry invented but imaginatively plausible losses; the grandmother, by contrast, is a model of maximal freedom — even excess. Between these poles, a field of tension emerges that speaks less about family than about narratability itself: What may origin be? What can be replaced? What can be invented? What should remain open? The series does not answer these questions. It poses them by testing, bending, expanding, and gently exaggerating the forms of genealogical thinking.

It is precisely in the difference between the three figures that the melancholic yet humorous tone of the series arises. Ancestral Research is neither historical reconstruction nor fanciful lie, but an inquiry into the forms in which identity can emerge when history is treated not as burden but as material. Violence does not disappear — it migrates. And in this movement lies the poetic and theoretical force of the work.